10 May 2019

|

Jonathan Callaway provides a guide to collecting English notes and the wide range of possible collecting themes.

English notes fall into four main categories, dominated unsurprisingly by the issues of the Bank of England. Other collecting areas I will look at include UK Treasury notes; English provincial notes; and lastly Transition Town issues.

BANK OF ENGLAND

The Bank has been around since 1694 and issued notes from the outset. All the earliest ones are extremely rare and a new collector will most probably be looking at 20th-century issues. An ideal starting point would be 1928, when the Bank first issued its red-brown 10 Shillings and green £1 notes.

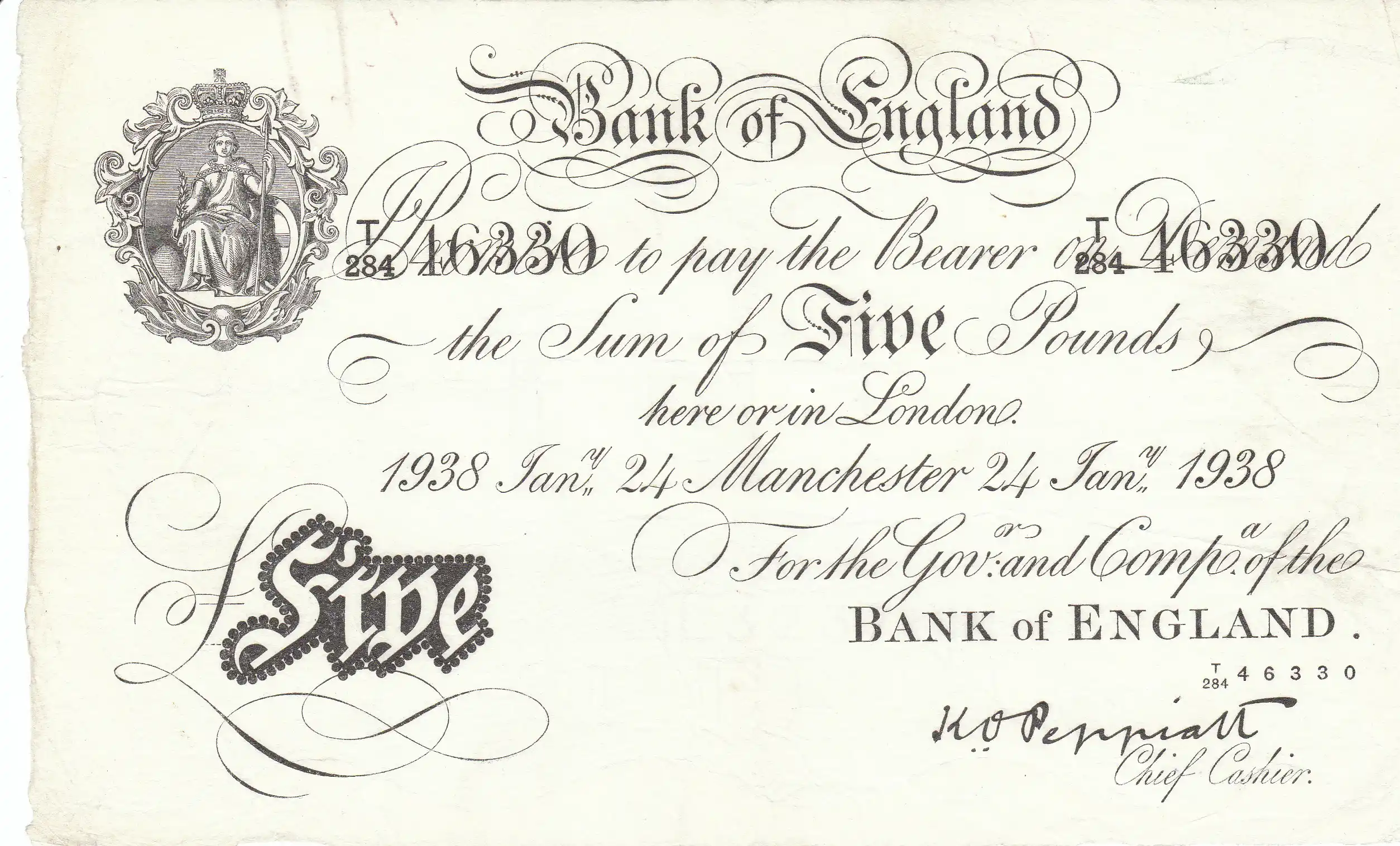

The new collector is always advised to keep it simple and this is good advice. Starting a collection by acquiring one of each of the major types is a good way to get a good feel for the Bank’s issues – and involves no more than 28 notes. This would include the famous old ‘white fiver’, a design which quite remarkably lasted from 1694 all the way through to 1956 and so-called because it was a simple one-sided note printed in black on white paper.

The first time the Queen appeared on the Bank’s notes was in 1960 when the Portrait notes familiar to most of us replaced the 1928 issues. Higher denominations followed and in 1970 we saw the first of a long line of notes with historical figures on the back – the £20 note featuring William Shakespeare. To date there have been seventeen notes with historical figures on them.

New collectors are also well advised to obtain a good recent catalogue and should then proceed to buy the best notes their budget allows, rather than bulking up their collections with too much lesser grade material. Beyond the basic note types collectors might seek to acquire ones with different Chief Cashier signatures.

Since 1928 there have been fifteen Chief Cashiers and a new one, Sarah John, was recently appointed to replace the current signatory, Victoria Cleland. She will be the third woman in this role and her signature is first likely to be seen on the new polymer £20 notes due for issue in 2020.

Beyond signature varieties collectors tend to look at first and last prefixes of each type, though the scarcer ones can be rather expensive. Prefix enthusiasts will also be keen to acquire replacement notes which until 2007 carried distinctive prefixes. Error notes have their following too.

White notes form a specialist field for some. All pre-1914 notes are scarce but those with deep enough pockets will be rewarded with a rich mixture of white note denominations from £5 to £1,000 (not to forget £1 and £2 notes from 1797 to 1826) and branch notes. The Bank once had some thirteen branches but collectors are highly unlikely to see more than eight of them, the others having ceased to issue notes many years ago.

All white notes keep to the same basic design created in 1694, with a small vignette of Britannia in the top left corner and copperplate-style text. Of course, engraving quality improved over the years and the Bank built in forgery protections through tiny detail changes and secret marks.

The arrival of polymer £5 and £10 notes has boosted interest in banknote collecting and some very serious prices have been paid for low numbered notes. The lowest numbers have traditionally been allocated to royalty (naturally the Queen gets the number 1 note of every new issue), senior political figures and top bank officials, while the Bank has offered others via charity auctions.

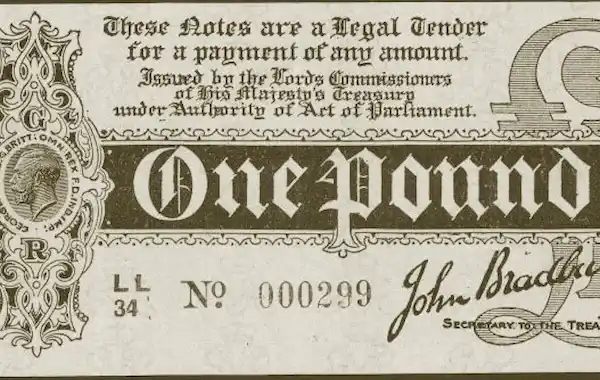

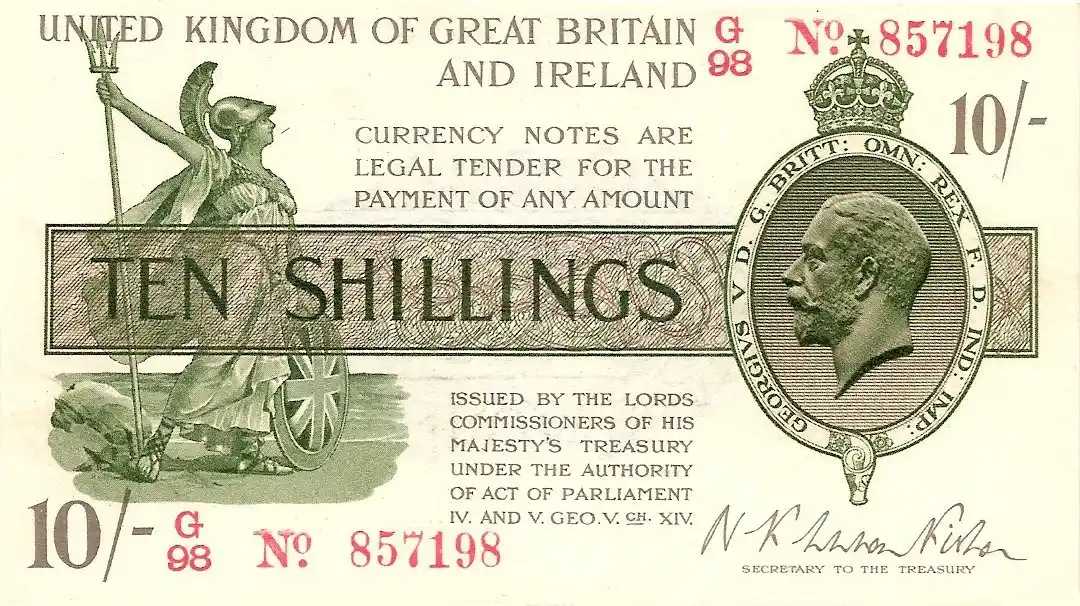

UK TREASURY

These are most often collected in conjunction with Bank of England notes. The UK Treasury issued 10 Shillings and £1 notes from August 1914 until 1928 when the Bank of England took over the task of providing these denominations. When the First World War started in August 1914 Britain was still on the gold standard, but this was immediately abandoned as a matter of financial necessity to preserve gold stocks. The Treasury notes were required to replace the gold sovereigns and half sovereigns which quickly disappeared from circulation.

Treasury notes come in six basic types, three for each denomination and due to the speed with which the first issues had to be designed, printed and distributed, they offer many minor varieties for the specialist collector. Most of the earliest issues are no longer cheap or easy to find but the third issues from the 1920s are still readily available. They form an essential part of the modern British paper money story.

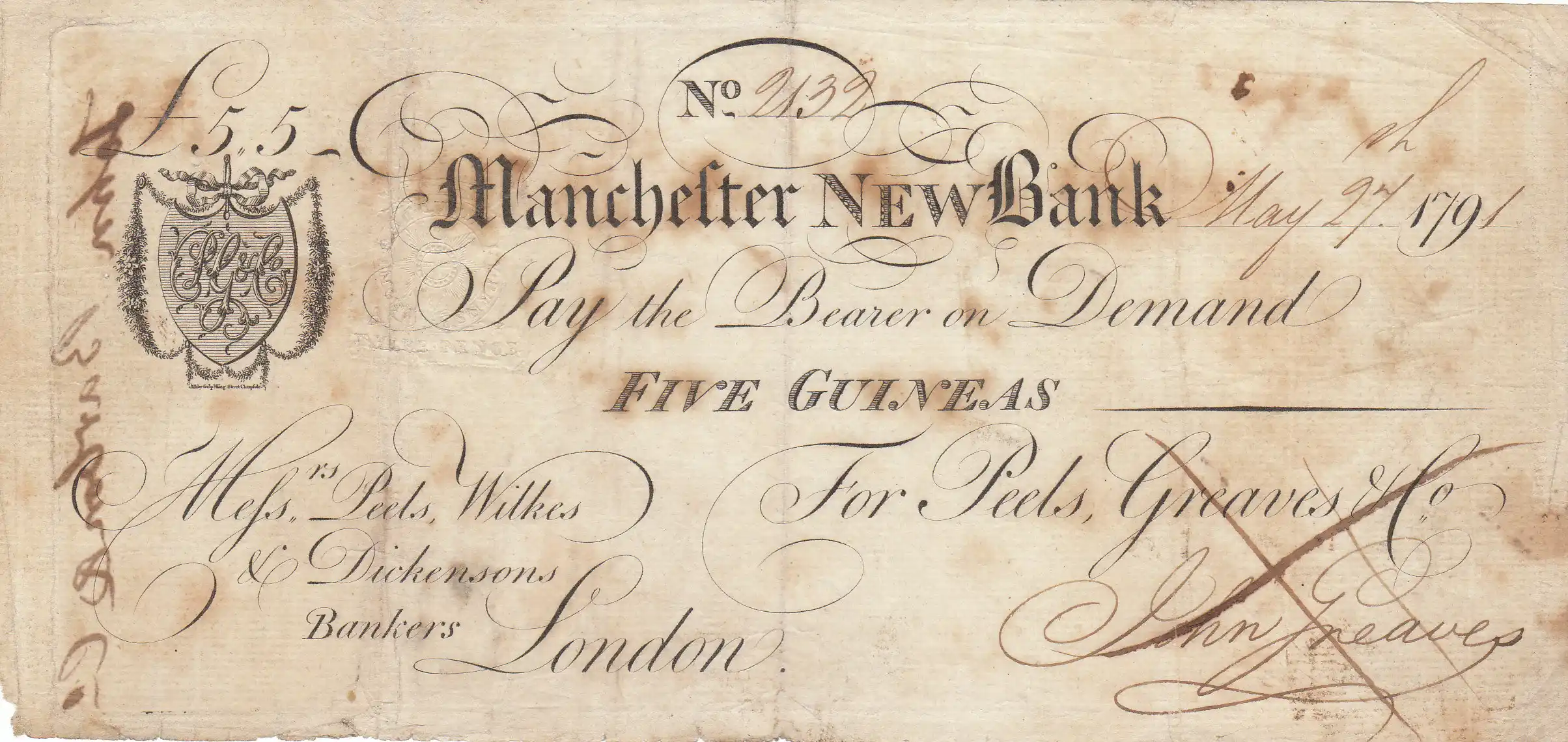

PROVINCIAL (OR 'COUNTRY') BANKS

A multitude of banks in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries issued their own notes. It seemed that just about every town in the country had its own local issuer. Most were small and often undercapitalised partnerships (the law limited them to six partners until 1826 when joint stock banks were first authorised). They started to appear when the growing demands of the Industrial Revolution required new sources of capital. The Napoleonic Wars brought about a surge in the formation of new banks when small change disappeared and an urgent need for circulating money developed.

Together these local banks constitute a huge field of collecting interest with banknote collectors often competing with local and financial historian enthusiasts. Many of the banks failed and their notes tell a story of mismanagement and disaster involving local businessmen and landowners.

Regular financial crises whittled away the numbers of these banks after these peaked around 1810, culminating in an acute crisis in 1825 which swept many away and finally forced the government to legislate. Once larger joint stock banks started to appear the writing was on the wall. The Banking Act of 1844 further restricted note issuance by private banks and 1921 saw the last of them finally give up its note issuing licence.

The most difficult notes to obtain tend to be the earliest, i.e. before about 1790, and the latest, i.e. those issued after 1900. Notes issued after the 1844 Act are generally scarcer while such notes often showed how banknote design was developing with increasing use of colour and more elaborate engraving.

TRANSITION TOWN ISSUES

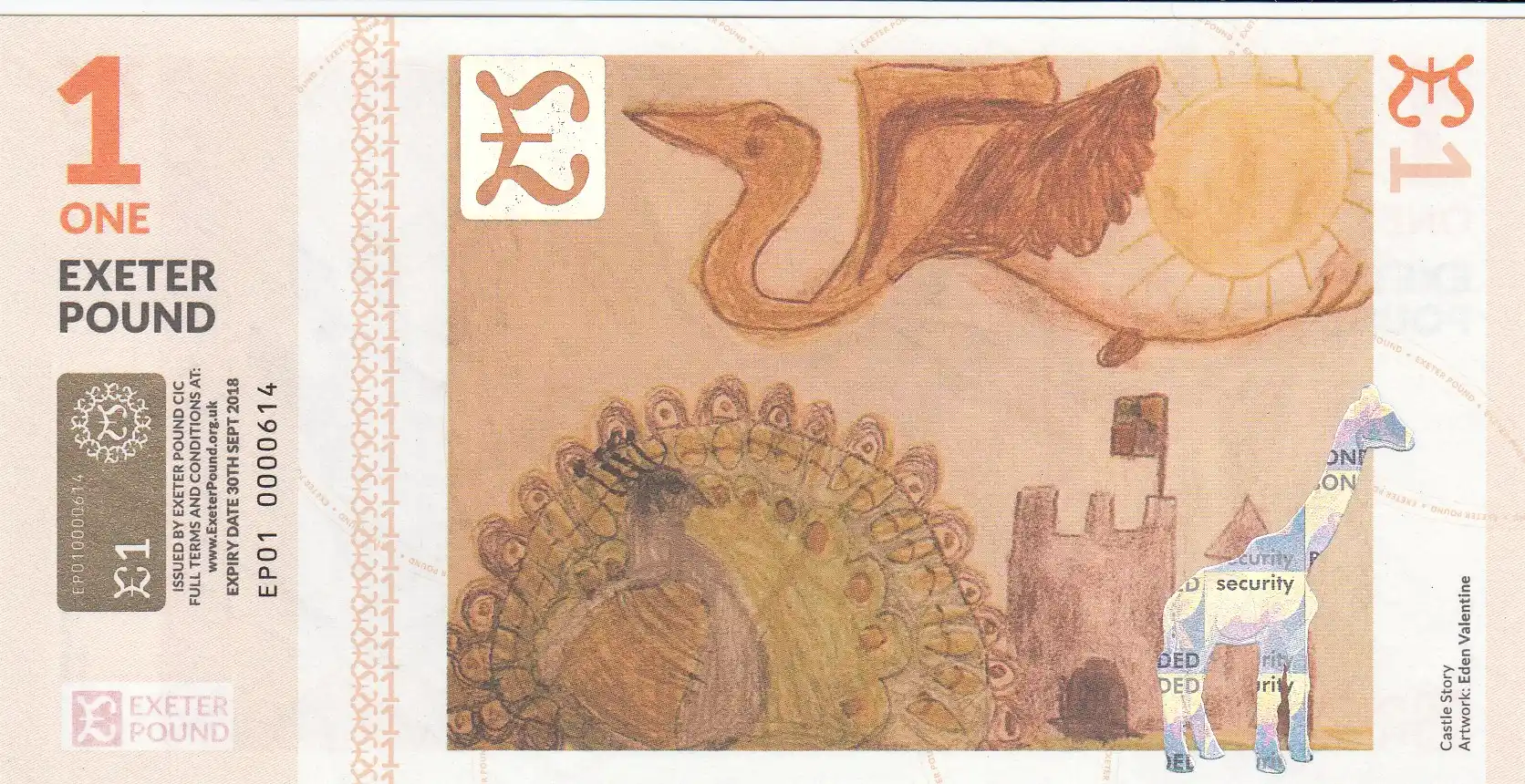

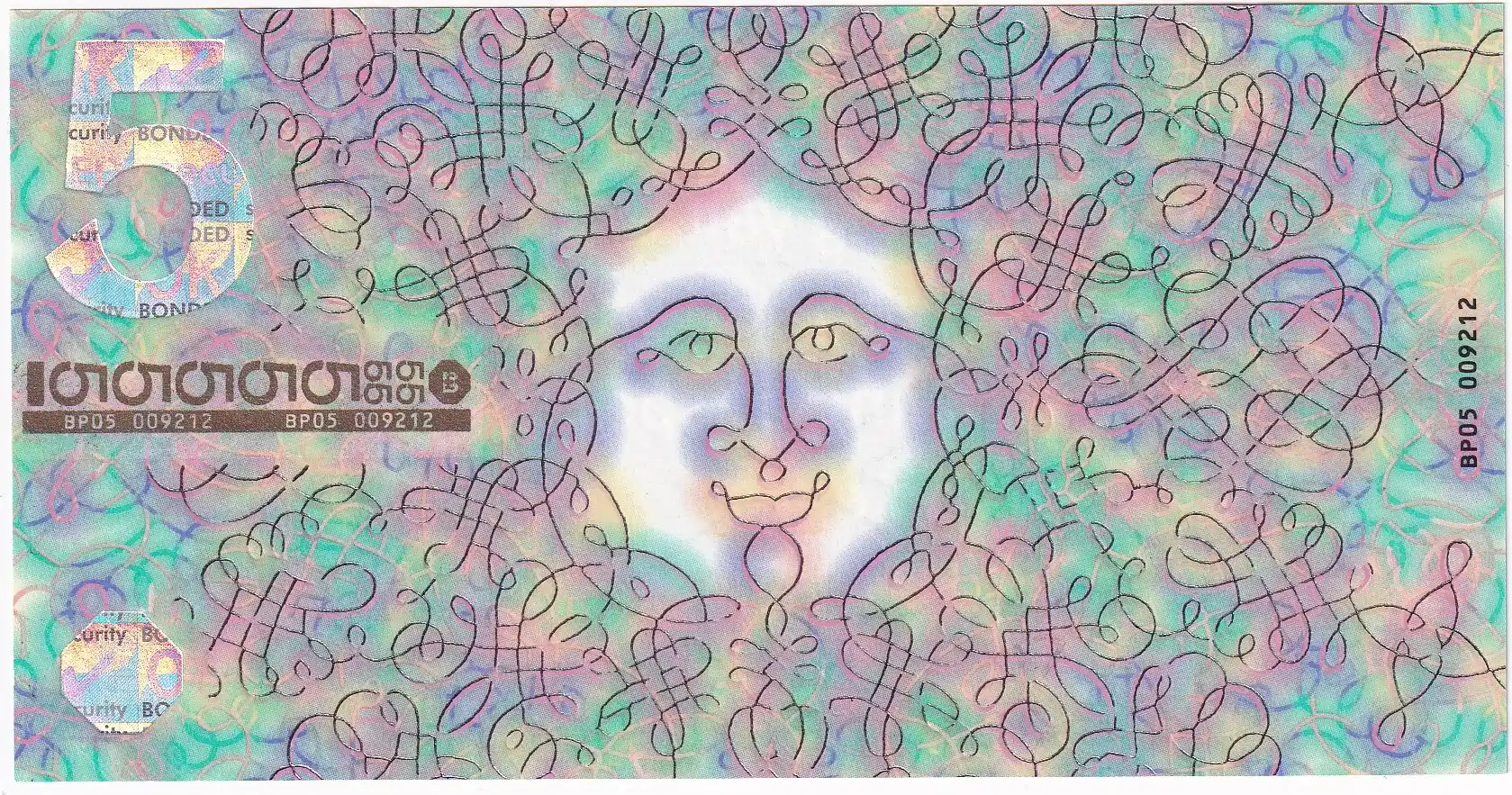

These are very much a modern phenomenon. The first English town to try its hand at a local currency was Totnes in 2007. The aim of the exercise was to keep local money in the local economy and reduce reliance of goods and food imported from further afield. Lewes was another early issuer of local currency though the largest in terms of circulation is now Bristol, with an average £700,000-worth in issue. Several other towns have followed suit but not all schemes have been successful leaving some notes hard to find.

Technically these notes are ‘trading vouchers’, most with expiry dates, and because they require conversion of regular currency to fund them they do not constitute an increase in the money supply, thus avoiding any clash with the Bank of England. Collecting local currency notes is increasingly popular and many of the designs are very innovative and colourful.

QUICK LINK: Your guide to English and Scottish banknotes